PROJECT TIMELINE

Phase A

Reconstruction of 12th Avenue North and 31st Street North Bridges

COMPLETE

Phase 1

Bridge Widenings on I-65 over 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Avenue North

COMPLETE

Phase 2

Reconstruction of I-65 and I-59/20 Interchange Ramps

COMPLETE

Phase 3

Reconstruction of RME Ramps and Reconstruction of Mainline Bridges

MARCH 2017-NOVEMBER 2020

Phase 3 (Milestone)

Closing of I-59/20 Bridges

APPROXIMATELY 14 MONTHS

59/20 BRIDGE HISTORY

17/03/11

Burying the Interstate

Space Constraints

The greatest issue to overcome is space. While there is sufficient width between existing buildings for the road itself, the space is insufficient to accommodate full shoulders, or to actually dig the trench – working slopes would be required, causing the “dig” to get underneath numerous adjoining buildings, weakening their foundational support. Additionally, once completed, it would be impossible to expand the roadway at a future date to accommodate the capacity requirements associated with the projected 20-year traffic growth.

Utility Relocation

There are a total of 72 major artery utility lines running beneath the 6,600-foot span of the interstate, comprised of 22 telecommunication lines, 21 electrical lines, 12 gas lines, nine water lines, and eight sewer lines. Sinking the interstate through downtown would create problems with safely rerouting each of these utilities, and would have added a minimum of five years to the project timeline.

Traffic Operations Issues

Connecting the lowered interstate to the existing interstate system would have required creating several hazardous curves and excessively steep road inclines ranging from 9% to 20%. In comparison, the grade on I-65 northbound from Hwy. 31 in Hoover/Vestavia to the Alford Avenue Exit is only 4.7%. ALDOT sees these requirements as causing significant safety concerns.

Storm Drainage

Sinking the interstate would have required a comprehensive drainage plan to cover all 546 acres of the sunken roadway. Draining this area by gravity is not possible because the proposed depth of the interstate would have been lower than the water table. Therefore, a pumping station would be required, and the long-term operational cost of this station would have come at the expense of local taxpayers.

Closure

Finally, burying the interstate would have required closing it to public use for an unacceptably long period of time – during most of the construction period, demolition, reconstruction, and for the extended period of time required to re-route the traffic and relocate the utility crossings.

17/01/11

Re-decking the Existing Bridges

In 2011, after consultation with the City of Birmingham and Jefferson County, it became clear that a simple re-deck would be insufficient to address the design deficiencies that currently subject motorists to persistent congestion and unsafe road conditions along I-59/20 through the Central Business District.

Reasons a simple re-deck is insufficient include:

No Shoulders

There are no shoulders on the current roadway, meaning emergency responders cannot remove disabled vehicles or address emergencies without causing traffic to stop.

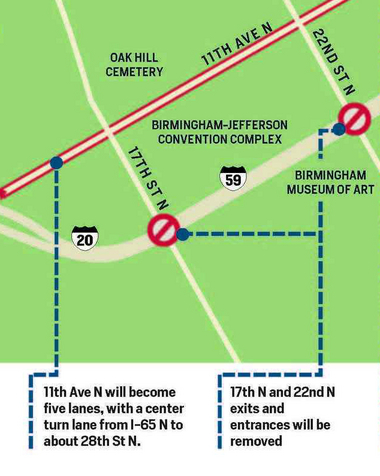

Weaves

There are multiple areas in the relatively short 6,600-foot section of the elevated structure where motorists are forced to “weave,” or make unsafe lane crossings, in a short distance in high traffic conditions. The two primary weave areas are the sections between I-65 and the 17th Street exit and between Red Mountain Expressway and the 31st Street interchange.

High Congestion

High congestion leads to unsafe driving. The bridges were initially designed in the 1960s to carry approximately 80,000 vehicles per day. Today, the roadway is traveled by over 160,000 vehicles, more than double the capacity set forth in the initial design. By 2035, this number is projected to exceed 225,000 vehicles daily.

Outdated Lifespan

The elevated bridge structure was originally opened in 1973, with a 50-year lifespan. Today, over forty years later, the bridge is crumbling and the design cannot safely accommodate increased traffic.

These conditions already result in regular accidents, and will only increase and worsen unless improvements are made. This is why ALDOT proposed the solution being implemented.

16/12/10

Finley Boulevard Relocation

The “Long Route” involved re-routing I-59/20 near Tallapoosa Street west across I-65 and US-78, before rejoining with the existing I-59/20 corridor west of Arkadelphia Road. It shared the same disadvantages and costs associated with traversing the Village Creek floodplain as the short plan.

However, due to the width required for this interstate “corridor,” and that it must have avoided the Burlington Northern Railroad Yard, ALDOT’s study shows the long route would have require the demolition of nearly all the businesses along the existing Finley Boulevard Corridor.

If planning were to start today, the long re-route would take at least 28 years to complete, and cost over $2 billion.

ALDOT did not believe either the short or long re-route alternative was achievable.

16/09/10

Short Finley Route

The “Short Route” runs slightly south of the existing Finley Corridor thus avoiding the need to demolish businesses along it. This plan would re-route I-59/20 from Tallapoosa Street northwest along the Finley Corridor, connecting to I-65 with redesigned interchange, then continuing along I-65 to the existing I-59/20 and I-65 interchange – a total distance of 2.5 miles. While the distance may seem short on paper, it has numerous problems.

One challenge was the requirement that ALDOT widen a 1.3 mile stretch of I-65 from the new interchange to the existing route interchange between I-59/20 and I-65 in order to accommodate all interstate traffic passing through Birmingham. Calculations indicated that this portion of I-65 would, at a minimum, need to double from four lanes to eight, in both directions. This lane expansion would require ALDOT to acquire and demolish large amounts of property in minority and low-income neighborhoods, including Enon Ridge and Fountain Heights.

Another unique challenge is the path of the entire re-route would run directly through the Village Creek floodplain, portions of which contain hazardous materials and historical sites. These conditions would have required ALDOT to construct an elevated 16-lane interstate through the middle of minority and low-income neighborhoods, at a total cost ranging in excess of $1.5 billion. Even if this were feasible, it would have required more than 20 years to complete.

19/07/10

Re-routing the Interstate

ALDOT explored the feasibility of other options when considering whether rerouting I-59/20 along the Finley Boulevard Corridor would be feasible.

The re-route alternatives included the completion of a new interstate adjoining Finley Boulevard Corridor, which the City of Birmingham has pursued unsuccessfully for more than 30 years due to challenges involving hazardous material sites, floodplains and federal regulations. Another option involved relocating I-59/20 along a longer route also involving the Finley Corridor.

A major obstacle facing these scenarios is the concept of environmental justice. In accordance with an executive order signed under President Bill Clinton, federal policy disapproves of building a roadway through a minority or low-income area if another satisfactory route is available. Specifically, “Each Federal agency shall make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations” (Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, 1994).

The practical effect of the federal policy makes it highly unlikely ALDOT would receive federal funding to relocate I-59/20 along the Finley Corridor, as these options would have required displacing and relocating many more families and businesses than the current project.